A Guest Article written by Vera F

Introducting the article

One of the things that distinguishes one classical guitar from all the rest is its rosette. Mine are created inspired by an old English craft called Tunbridge ware. From conceiving the idea of incorporating Tunbridge ware into the rosettes, to actually doing it, was a long, difficult but exciting adventure.

I collaborated with Vera, who created a computer programme which enables me to visualise the designs and create them far far quicker than with just pen and paper. The Tunbridge ware makers of the past would be absolutely amazed by this, as well as designers in other mediums, such as embroiderers, mosaic artists, etc . The programme not only enables easy conception of new designs, but also calculates how much of each wood is required to be ordered.

I asked Vera if she might write an article to detail the fascinating adventure we went on, and the work she took on, to make this idea a reality. The programme was created completely from scratch. I am still stunned that this was possible! I hope you enjoy the read. Michael Edgeworth

How a Pile of Tiny Squares Became a Guitar Maker’s Secret Weapon

Pixels. Pieces of wood. Python. How does it all come together? And how does this relate to guitars? Let me take you behind the scenes and reveal to you what goes on during the making of guitars, and not just under the hands of the guitar maker Michael Edgeworth. Let us just take it step by step.

A classical guitar. An amazing result of craftsmanship. Its current appearance is the result of the work of thousands of luthiers and guitarists who have influenced its development for centuries. Its shapes, its curves. There is also something that catches your attention more than other parts. That beautiful ring around the soundhole, called a rosette. At first sight it looks almost magical. It appears like the fairy-tale elf came to life, sat down one night and glued hundreds of tiny wooden squares together in a perfect mosaic. But the truth is more prosaic: behind every rosette is a lot of patience, craft and … even a little bit of Python from nowadays. 🐍 But let us not get ahead of the story.

At the beginning of this story stands a discovery of the dead art of Tunbridge ware, an English craft from the 19th century in which artists used thousands of tiny wooden pieces to build detailed mosaics placed into furniture. To go deeper into the art of mosaic pictures and gain an insight into it, Michael (the guitar maker) and I had to travel to the town in the UK where the Tunbridge ware art was invented. Together we visited places where these mosaics are now displayed, admired the precision of those old craftsmen - who did not use modern technologies for their manufacture - and came back with our heads buzzing with ideas.

It did not take so long after when Michael grabbed his pen and the same old-school way, how the old craftsmen used to do, drew his first design on the paper. Later, afterwards, it was my turn when I joined the adventure: to turn those sketches into a working wood pattern editor. A functional program that could help him experiment with designs without wasting neither time nor wood. Without a need to count how many pieces of wood he would need and recalculate it every time when he would make a change in his design. And give him a safe playground for creativity.

After, what came next was not only programming, but a whole journey full of bugs, jokes and “I see!” moments during our collaboration. And in the end, there is a small tool that helps a real wooden mosaic creator, who breathed new life into old almost dead Tunbridge ware art, and a guitar maker in one person design his rosettes in a completely new way and take rosette designs to a whole new level.

The Challenge

As is usually when you observe something that comes from the hands of a professional you get the feeling that it must be simple and easy to imitate. But the opposite is often true. Behind it is loads of precise work, failed attempts and many sleepless nights. It is no different in the case of designing a guitar rosette. We will not just admire the final result, but we will make a sneak peek behind the curtain because making the rosette is like making a jigsaw puzzle in miniature. Each piece is a tiny wooden square, smaller than a pinhead, and together they form a mosaic pattern surrounding the soundhole.

Put yourself in this situation:

You use natural wood and you need to use different shades of brown (light, medium, dark and everything in between) because you want to bring depth to your rosette design.

You must know exactly how many pieces of each shade of brown you will need to cut because in the field of production of wooden musical instruments wood is precious and mistakes are expensive.

And as soon as you glue the wooden pieces together, there is no undo button. Wood does not forgive you.

Even more, some shades of brown are so similar. How to avoid getting a headache from it?

For centuries craftsmen solved these problems using just designs drawn on the paper. They needed a lot of practice and probably a big portion of patience (and coffee? ☕ 🙂). Michael started as the old experienced craftsmen did: his first design came to life only on paper, created carefully by hand.

But the real challenge came later: how to experiment safely without wasting wood and time by drawing while still keeping the freedom of creativity?

That was the moment when the idea of a digital wood pattern editor was born. A tool that could turn the headache of counting shades of brown and squares on the paper into a playful experience because the program would do it for him.

Enter the Pattern Editor (and me) to the Scene

At the very beginning the “pattern editor” was nothing more than a dream and a blank screen. And my tools? Programming skills in Python and a stubborn desire to see how Michael draws his pattern on a computer, how his design ideas come alive by clicking the keyboards.

The first version of the pattern editor was silly: a grid of white buttons that could only change by clicking into one colour: bright red! Not a very “wooden” colour, isn’t it? But hey, it was a start! 🎉 From this point, every day became a little coding adventure:

The shades of brown appeared, carefully adjusted to make the program reflect real wood tones.

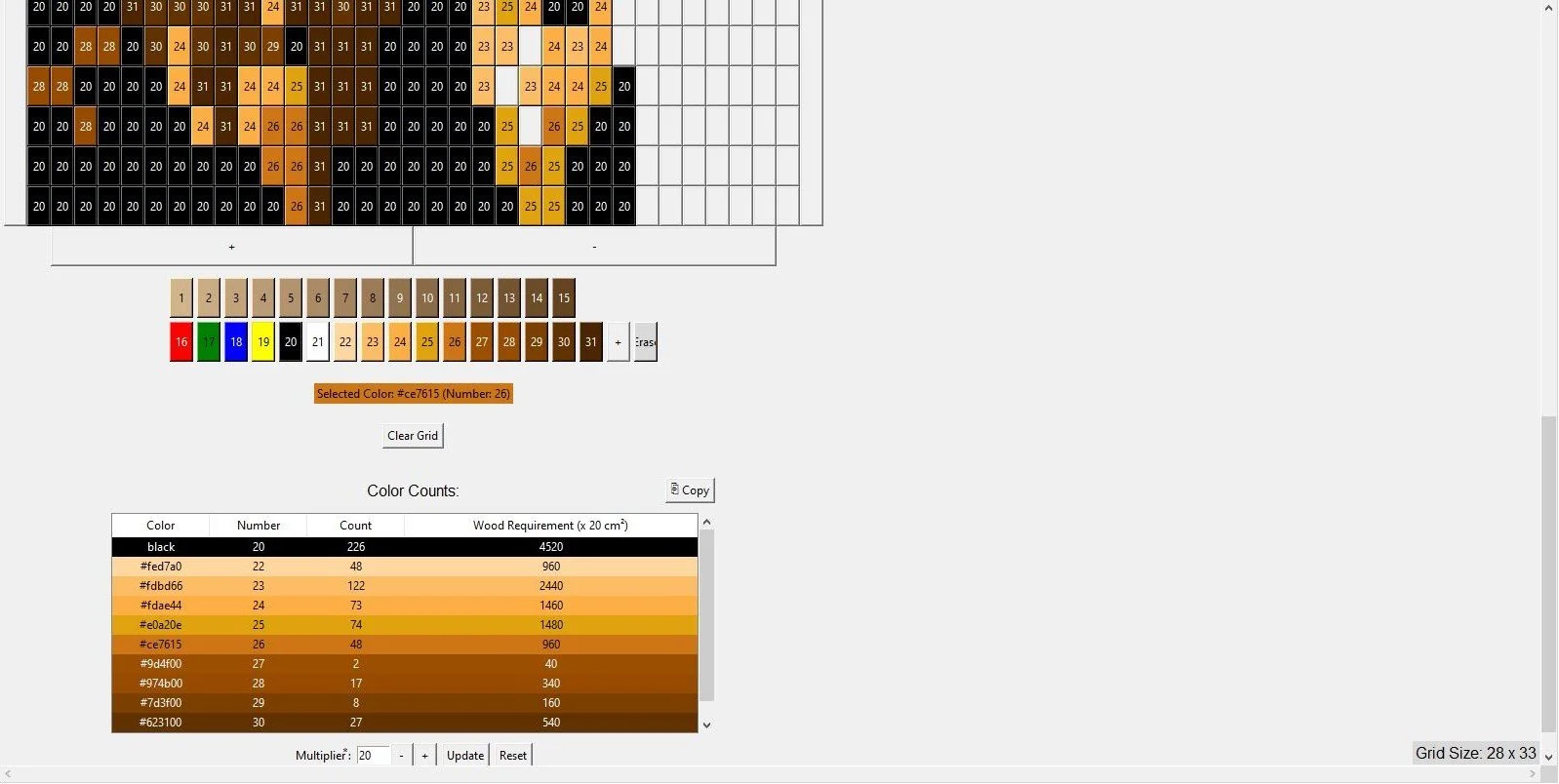

A counter showing how many tiny wooden pieces are needed for the pattern’s design itself tells Michael how many pieces of wood will be needed.

Then came the Undo/Redo function, because - let us be honest - mistakes are part of life (and coding too 😉)!

And of course, a Save/Load option, so Michael’s designs just do not disappear into thin air when he turns the computer off.

And there is much more but these are one of the most important. You do not have to be a soothsayer to guess that not all experiments during programming went smoothly. Some days the program behaved like a mischievous leprechaun would settle inside. Judge yourself:

“Ghost colours” appeared out of nowhere 👻 and haunting in the grid.

The scrollbars rebelled and refused to cooperate.

The Undo/Redo function acted as if it had its own artistic vision and ignored what I had really clicked before.

Now it sounds funny, but I was not in the mood to laugh at the time… But slowly, after many bug hunts and little victories, the pattern editor grew into something useful. What started as a simple red-squared toy turned into a genuine tool that Michael can use for his rosette designs.

Collaboration

Every good project needs its user and feedback. In other words it does not happen in isolation. It was not just about me and my code. It was about working hand in hand with Michael, the luthier. He had the vision, I had the laptop. Together we were like two sides of the same coin: wood and Python.

From the beginning Michael gave me some feedback that shaped the app in unexpected ways. He would be exactly the one who would say something like this:

“Could the app have exactly 15 shades of brown?” (Not 14, not 16. Fifteen.)

“Could the program count how many pieces of each shade of brown I will need?”

“I use Windows. It must run on Windows, otherwise it will never leave your laptop!”

So I had to learn how to ask him good questions, to test the program by drawing some designs (can you imagine me as a new wooden mosaic creator? 😅) and sometimes to fight with GitHub branches (some version tool where you can keep the versions of your program) late at night just to make sure he could download a working version (not that the uncompleted one with the uninvited mischievous leprechaun inside! 😱).

And as you expect together we celebrated the milestones like:

When Michael finally got access to GitHub!

When we agreed on the MIT license (after hours of research about software licenses that sounded like legal riddles 🧩).

When I presented the first working versions of the program. 💪

And most of all: the magical day when the program finally started to run on his Windows laptop without errors. At first it did not. At second it did not. At third it did not… but then, suddenly, it worked! 🤯🎉 (This is how we spent Easter holiday!)

Collaboration is not just about finding ways to make things together. In our case the collaboration also meant to travel together! Our visit to Tunbridge Wells during which we were exploring the roots of Tunbridge ware art, was not only inspiring and I will remember it like the beginning of this adventure, but also gave us a sense that we have been carrying a little piece of history with us forward. From museum showcases through Michael’s workbench to my code editor. The tradition lives on - it just changed the medium!

The Result

After weeks of coding adventures, bug-hunting and Michael’s steady stream of ideas for improving, the official first version of the wood pattern editor finally became what we dreamed of: a practical, playful tool for designing mosaics for rosettes.

With it, Michael can now:

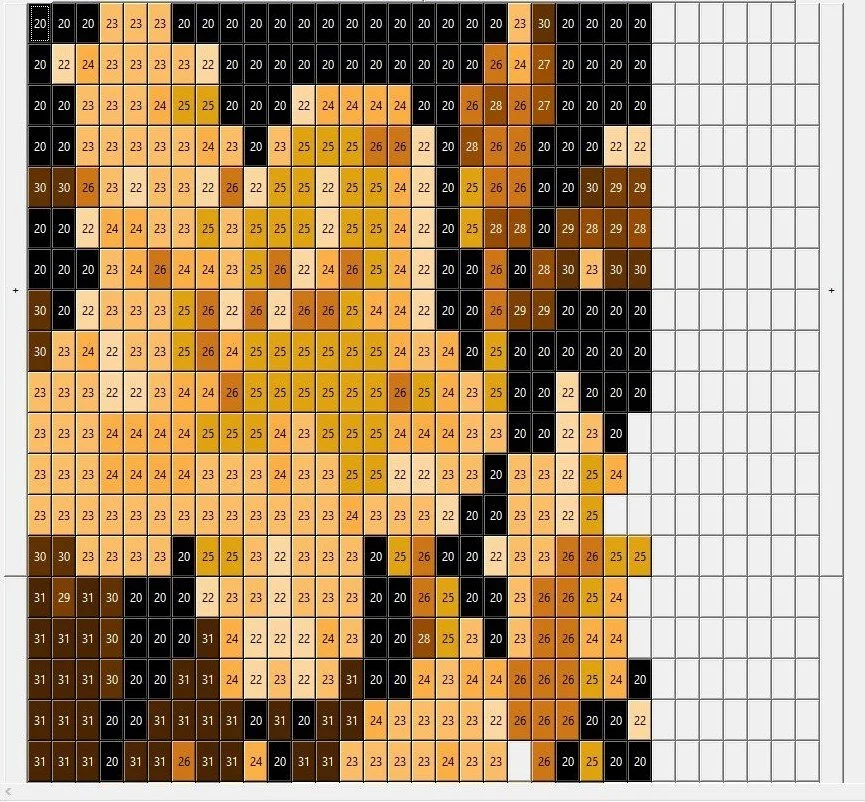

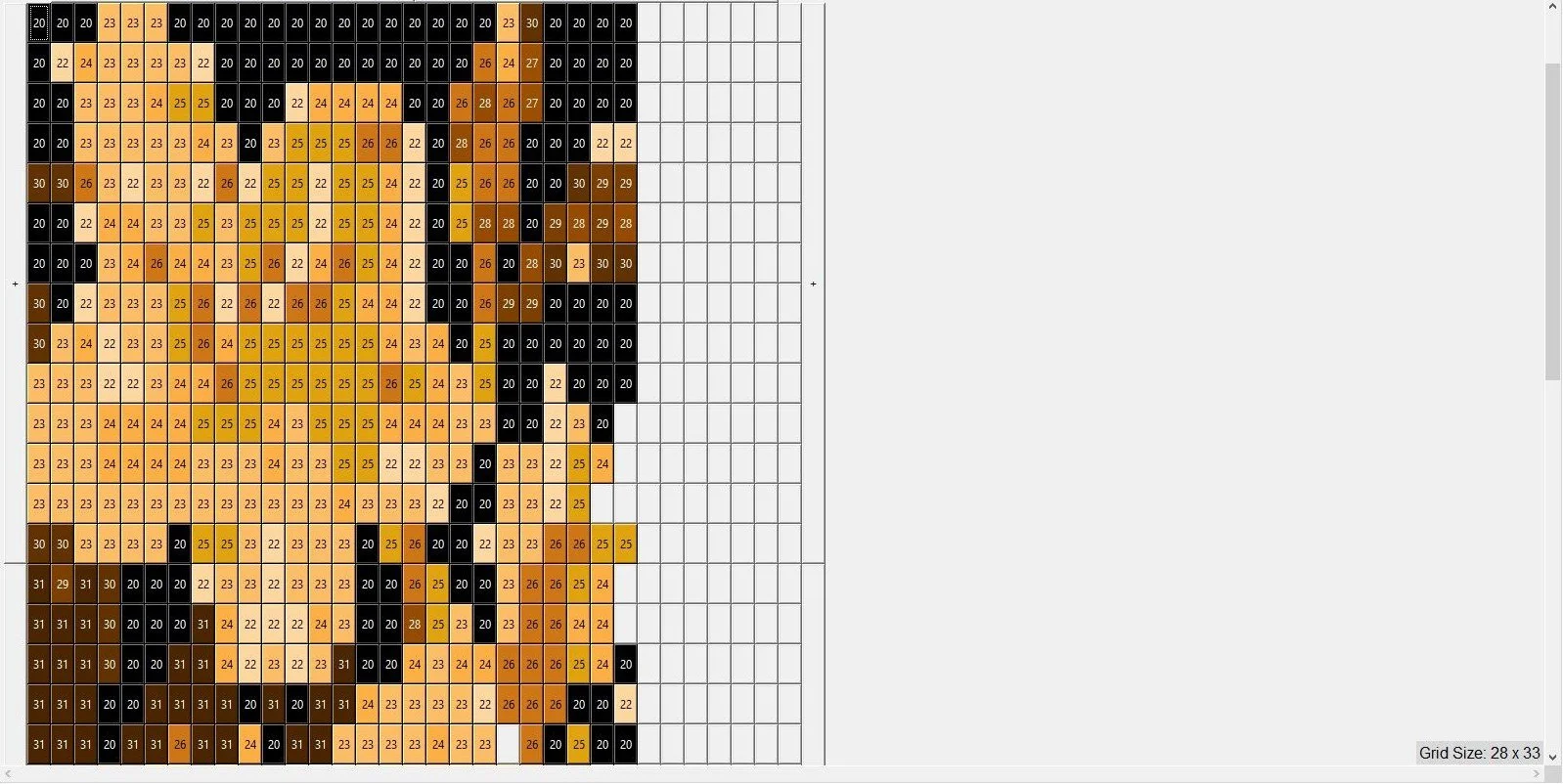

Design rosettes digitally by clicking on a grid of squares using 15 shades of brown on the basic level.

Experiment with colours - not only with shades of brown but also custom shades if inspiration calls or a new colour of the wood is on the horizon. (It is unforgettable when we discovered wood infected with the green elf cup fungus which causes deep green-blue veins to run through the wood!)

Play endlessly with designs - different shapes and combinations of colours before ever touching real wood.

Know exactly how many pieces of each shade he will need for a design: so no precious time or wood will be wasted.

Save and load his experiments, so ideas do not vanish and he will build a personal powerful library of rosettes.

And suddenly, what once required hours or maybe days of careful drawing with pencil and paper and precise calculations of squares now happens with just a few clicks. Most importantly, the program itself does not want to replace the Tunbridge ware art - it simply gives the artist, the wooden mosaic creator, freedom: the chance to test new bold ideas without fear, risk or limitation. In the safe playground of the editor, Michael can undo, redo, change his mind, start again, experiment… Just do things that would be impossible once real wood is glued and held together tightly.

And yes, making designs in the editor is not only functional, it is also fun! To watch how the rosette patterns grow square by square reminds the painting pixels in an old-school video game. Except for that the final artwork will end up on a concert guitar! 🎶

And the proof? Here is one of Michael’s rosette designs created inside the program: (this will be updated shortly with a full pattern example).

Looking at the screen you see the grid of numbered and coloured squares. But can you imagine that in Michael’s hands those little squares become strips of wood, precisely glued one by one into a rosette? The design of the pattern is only the beginning of the work. The program only makes part of the whole process of creating the rosette easier. It gives the guitar maker a powerful tool but the greater part of the real work remains with the artist. Only he can transform the design into a real rosette that gives the guitar its unique signature.

Reflections

This whole journey reminds a building of a rosette itself. Little steps, many small pieces, a lot of patience and at the end there is the program - a pattern that makes sense. Michael brought the tradition, the eye for beauty and the craftsman’s precision. I brought some Python coding, stubborn debugging and curiosity. Alone, we could not create the program itself, but together we turned the old art into a living, modern, evolving tool.

Looking back, what started as a design on a paper became something more than just a tool. It became a bridge. It was not just about writing a program or just about building a rosette. It was about how two crafts meet halfway.

On one side there is the several centuries old craft of lutherie, where patience and tradition rule. Where hands of a luthier shape wood into music. On the other side there is a young craft of coding, where logic, testing and a bit of Python magic takes over. Where the fingers of a programmer dance across a keyboard to shape the app to breathe life into logic, into code containing numbers and symbols.

Two crafts. At first glance, they could not be more different: they use different tools, different materials. But both crafts share the same heartbeat: patience, precision, beauty, imagination and creativity. One of them shapes a guitar, the second one shapes an app, and both of them struggle with details, polish the edges and try to achieve harmony in the final result.

The wood pattern editor now stands as a bridge between these two different worlds. And definitely it is not meant to replace the human hand or maker’s artistry. It lets a guitar maker explore designs with freedom. It gives space to experiment, to play and to imagine without limitation. And even more it keeps the spirit of Tunbridge ware art alive to show up to the world in a new form: this time in the rosette of a guitar.

It is not the end of the story. The program keeps evolving as every good craft does. There are always new ideas waiting for implementation and polishing: AI, better interfaces, more colours, more possibilities…

In the end, what started as an experiment at the beginning has become something greater: the proof that when two craftspeople collaborate, the boundaries between two different worlds blur and something new appears: the harmony between tradition and innovation.

Pixels, Wood and Python code. An unusual trio. But together they can tune long before the strings on the guitar do. 🎶